Sara Davidson

|October, 17, 2019

In July, when I told friends I was taking a tour of Ukraine and Moldova, they were baffled. “Why?” they asked. It sounded like vacationing in lower Slobovia.

We did not know—at that exact time in July—that President Trump was pressuring Ukraine’s President Zelensky to dig up dirt about Vice President Biden, nor that in a short time, Ukraine would be leading the world news.

So why, indeed, was I going? Well, my father’s parents came from Odessa, which was then part of Russia though

now it’s in Ukraine. I was curious to see the Jewish quarter where they’d lived, taste the dishes they’d eaten, like gefilte chicken neck, and look out at the Black Sea.

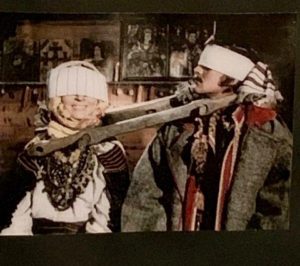

Traditional wedding deep in Ukraine

But the real reason was that a friend from my days at U.C. Berkeley, Tracy Johnston, had invited me to come. At Berkeley in the 60’s, Tracy was a much-admired beauty, smart, funny, and adventurous. She taught me how to backpack in the Sierras, when no one else I knew had ever backpacked. I remember we staged a water fight in a pristine mountain lake, because we’d seen guys engaging in hijinks and… why not us too?

After graduating, I moved to New York, later to L.A., then Boulder, but Tracy stayed in Berkeley. We’d hardly seen each other for decades, but in a rare call, she said she was going to Ukraine with a company she likes traveling with, Wild Frontiers, based in London. “Want to come?”

She said they specialize in trips to places where tourists rarely go. She’d gone with them to Pakistan and Madagascar, where they’d met a family of hunter-gatherers who didn’t own a cooking pot.

“The people who take these tours are good travelers,” she said. “They’re adaptable and don’t complain.”

“I’m a master at complaints,” I told her. Laughing, Tracy said she was excited to see the street art of Kiev, the fairytale-like city of Lviv, and the Carpathian mountains. None of that was calling me, but I did want to see Odessa, so I told Tracy that if I could get flights at a reasonable price, I’d go. I was pretty sure at this late date—weeks before departure—costs would be prohibitive.

They weren’t (which should have told me something), and on July 28, I was in Kiev, meeting Tracy and her friend from a previous trip, Betty from Cincinnati.

Swingin’ Ukraine

I knew that landing in a foreign country fires your senses, heightening your awareness of the life around you. The flood of new stimulation wakes you from the slumber of the familiar—the world to which you’re so accustomed that you no longer notice details.

But I’d never been a fan of group tours. I don’t like set schedules, staying at a different place almost every night, and having to make conversation with people I might have little in common with. Those on the tour, though, said it saved them endless hours of research, booking hotels, flights and trains, and finding places not to miss. It freed them to just pack and go.

On our first day, the group drove to Chernobyl, which has been overrun with tourists since HBO aired its series on the disaster. I wasn’t convinced Chernobyl was safe. Visitors were instructed to wear closed shoes and not touch the ground, since it could be radioactive. What if I tripped and fell? I have crummy balance.

Instead, I hired a young woman guide to show me around Kiev, which my grandfather had often visited. I asked her where we could find the best borsht in the city. She took me to the restaurant Kanapa, on the steep, curvy street called St. Andrew’s Walk, and the soup was delectable. No other bowl of soup we would eat on this tour would come close. It contained the juice of fresh summer fruits along with beets, carrots, pork, finely-sliced cabbage, onions, and dill, but it was the plum and cherry juices that made it sing.

The tour did not stay long in Kiev, but moved out to the promised frontiers: towns and villages whose names I couldn’t pronounce then and can’t remember now without consulting my notes.

Eggs at museum

Our group would not be taking that risk—our eggs had already been drained through a pinhole. We began by heating a beeswax-covered egg over a Bunsen burner, drawing designs with a stylus, then dipping it in red dye. The lines that had been drawn would come out white while the rest of the egg would be red. Then we’d draw more lines and dip into two different colored dyes.

The next day, according to our itinerary, we were supposed to take “some easy walks” in the Carpathian mountains. It had been raining for days, and the trail was steep, slippery, muddy, and rocky. Luckily, our guide had ordered two ATV’s driven by Ukrainian soldiers for myself and another who preferred to ride than take the “easy walk.”

We sped straight up the mountain, using modern machines to ride back in time. There were no signs of civilization as we climbed and dipped, passing chartreuse-colored meadows covered with wild flowers. This was the land of the Hutsuls, a tribe who’ve preserved their traditional ways over centuries. Our guide, Igor, said the Hutsuls live in the valleys and in summer, take their cows to the grass-covered mountains where shepherds milk and care for them so the farmers can tend their crops.

We screeched to a halt by a rustic cabin, where shepherds were making their traditional Brynza cheese in a giant iron pot, hanging over a wood fire. “The Hutsuls are very superstitious,” Igor said. “They keep the fire going all summer, and if it goes out, they take the cows somewhere else.” Betty asked why, and Igor said, “If something has been done the same way for centuries, that’s the reason to do it.”

Lunch was spread on a long wooden table outside. There was the fresh Brynza in three different stages of fermentation, one mixed with cornmeal like polenta. We passed trays of tomatoes and cucumbers picked nearby, fresh baked bread, and bowls of creamy beige honey the consistency of mashed potatoes. There were two homemade wines, purple and gold; it was one of the best meals we had.

Meals were the most challenging part of the tour for me. Both lunch and dinner began with multiple platters of cheeses, cold meats, fish, bread, and salads passed around. I never knew how much to eat and how much room to save, because after the platters were cleared away, out came hot dishes, though we never knew how many: roasted meats, grilled fish, noodles, dumplings, and potatoes. Then dessert. We all agreed it was TMF—too much food. My stomach started to bloat, and I tried to eat less, but we sat at the table for hours and will power has never been my long suit. Igor said, only half joking, “The idea is, they keep bringing food until you say uncle.”

After lunch, we visited a traditional Hutsul home built of thick logs. It was dark and claustrophobic, but it kept out the cold or heat. Inside were looms so they could weave and sew their clothing, a fireplace for cooking, primitive tools, and musical instruments. On the wall I saw a photo of a Hutsul wedding. The bride and groom were blindfolded and bound at the neck by a wooden yoke like those used for working cattle.

It was a shock to see, but later seemed an appropriate metaphor: love is blind, and, as John Cleese once joked, he and his wife had been “manacled together.”

Coming down from the Carpathians, we crossed the border into Moldova, a land that’s been fought over since the beginning of history. Our new guide, Natalia, said the land in Moldova is desirable because it has a sunny climate, fertile soil, fresh water from underground springs, and natural barriers of limestone cliffs. In one lifetime, she said, a person may have experienced seven changes of nationality, as Moldova was overtaken by Romania, Poland, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. “With each change, there was a different language, different government, and different papers required,” she said.

In Kishinev, the capital of Moldova, Jews made up 46% of the population before World War II. The Romanians, allied with Germany, invaded the country and marched all the Jews—half the population—to camps, forcing them to wear nothing but thin clothes at the height of winter. Those who made it to the camps were shot or burned.

Natalia said, “I think every Moldovan has some Jewish blood, because Jews were here at the time of the Romans, in 200 AD.” Today, however, the majority of Moldovans are blonde with light eyes. After a week in the country, I must say that Moldova has the most beautiful women I’ve seen in one nation. Most have bright blonde hair, fair skin, beautifully chiseled features, slim legs and tall bodies. On a dirt street in a remote village, I saw a girl, probably in her twenties, talking on her cell phone, wearing shorts and a halter, whose natural beauty was so astonishing I had to stop and take it in. If she’d been standing on Sunset Blvd, she would have been recruited to be a model or actress.

Men come from all over the world, especially Italy and France, to meet Moldovan women and bring them home to marry. In a guesthouse where we stayed, there was a group of ten Italian men who’d come for that purpose.

Natalia, who had a long-term relationship with a man from Australia, explained, “The men come first as a tourist, then come back to Kishinev where there are lots of single women who don’t want to live in the villages where they were raised.”

Crossing back to Ukraine, we at last reached Odessa, where it seemed as if a dark screen had been drawn over our sight. The blondes of Moldova gave way to people who, almost universally, had dark hair and dark skin. Their ancestors had been Turks, Greeks, and Italians who’d settled the land along the Black Sea. The city of Odessa, however, was not founded until 1794, by Catherine the Great, who wanted to create a warm-water harbor that could export grain all year. She offered free land to people who would settle and build houses there. Jews poured in, having been banned from living in Moscow or St. Petersburg. It was like the Wild West; young men came to make their fortunes. Parts of the city were controlled by a Jewish mafia as treacherous as the Sicilian. To survive, people had to have a sense of humor and tough skin.

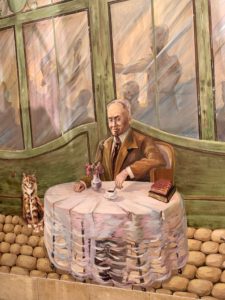

Odessa was a hotbed of socialism, communism, and Zionism. Trotsky was born there, as were Golda Meir and Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a founder of the state of Israel. But in Odessa, Jabotinsky is revered for writing what’s considered “the great Odessan novel”—The Five. Odessa was the only city in Russia where Jews strived to assimilate, and in The Five, Jabotinsky follows a family for whom the early 1900’s “were like spring.” Feeling optimistic and free, they built grand homes, made vast sums in the grain industry, and patronized the finest cafes, theaters and opera. They gave their children secular educations, but only 10% could be accepted for advanced degrees because the government did not want too many doctors, lawyers and professionals to be Jews. Kids who couldn’t make the top 10% went to celebrated music academies. It was said that if you saw a Jewish boy on the street who was not carrying a violin case, “he played piano.”

After pogroms in 1903 and ’05, Jabotinsky urged Jews to arm themselves, but masses, including my grandparents, left for America. The dream of assimilation was utterly destroyed by World War II. Jews had made up 35% of Odessa’s population and today, they’re less than five.

Do I wish, during our tour, that we’d known what was going on between Trump and the Ukrainian government, so we could have heard local responses? Sure. But in our ignorance, we had a merciful vacation from the toxic, round-the-clock news bulletins screaming “Ukraine,” which began shortly after our return.

Scandinavian saunas

Pool at the Ark

And I look forward to my next destination—Tanzania.

Hey Sara – that was FUN to read and to remember and re-learn some of the history I forgot. You left out the bad parts (the group was a bit boring; there were too many churches, and I was never actually beautiful) but you are right – you never complained. You were a great companion on the trip. As for the food – there was indeed too much, but I bet, with all that walking, you didn’t actually gain much weight.

The Jewish history was super-sad for me, not only because of the horror. My grandparents were German (they came to New Yorkt in the late l800s). My people. My shame. And remember we found out about Holodomor – where 4 million Ukrainians starved to death in l932 and 33 after the Soviets confiscated all their wheat.

But I have to stop. You are now the writer. Onward to Tanzania!

Thanks,Tracy. It was worth going just for us to connect. It’s an interesting question you raise about shame. Are we to feel shame for all the atrocities the US has committed in its history: the Vietnam war, atrocities committed by US troops to native Americans, slavery, etc. I feel sadness and grief, but is the shame inherited, genetically or psychologically? I certainly believe some reparations are due. But feeling shame is not useful to oneself or anyone else. I’d like to hear from others about this? Please join the conversation.

I feel more shame today with what our president is doing; we talk about corrupt governments around the world. The shame I feel is about the corruption in our government today, the recent Syria situation, etc. And I do feel responsibility for the Vietnam War and all those who suffered. Slavery & our treatment of Native Americans is still apparent and though I may not have been personally to blame, I feel as an American that we need to admit and acknowledge what our country has done.

And I loved reading about your trip, especially the Odessa part. And I was remembering a brief trip I had made to Kiev back in the 80s. Thanks!

Such a wonderful post, Sarah, so richly informative and entertaining, and as colorful as the painted eggs!

How wonderful. What an enjoyable read! You are such a good writer-

Sara, thanks so much for taking me one your Ukrainian adventure. I loved every word because that part of the world is not on my bucket list.

It was not on my bucket list either! Kurt Vonnegut wrote, “Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God.” I’m glad I responded to the peculiar one I received.

As usual, ur writing is always succinct and alarmingly fresh. I STILL would love to see u write a sequel to “Loose Change” – a life-changing tome for me!

Hi, Sara!

Great travelogue blog!

Some of what you wrote about reminded me of the two times I went to Georgia (the country, not the state!) to film, and then a few years later, to see the Georgian premiere of my documentary BOTSO. (I was the writer and producer… http://www.botsomovie.com)

The meals were similar, with soooo much food that just kept coming and coming. Georgian women are also gorgeous, with dark almond eyes and lighter features…. a mixture of east and west. We also did a long hike one day up a mountain, and nearly got killed. All for the sake of a movie–ha!

And the Easter eggs! I’m sure you know this part of NYC well, but I lived in the East Village on 10th Street in the late ’70s, right in the heart of what was then a Ukrainian neighborhood. And last year, I visited Chicago for the first time and stayed in an AirBnB adjacent to the Ukrainian Village neighborhood–there are some great delis there and exquisite churches.

Fascinating trip, but what did you learn about Joe Biden?

(Only kidding, only kidding.)

Thank you.

I deeply appreciate you sharing a personal journey with your wonderful writing voice, Sara. You are a very gifted wordsmith. My family also migrated from Odessa/Kiev to America after the pogroms of 1903 and ’05. They first made their way to become cattle farmers in New Jersey (Really??). They then continued on their way to Western PA where I have my own roots, and I went to graduate school. The next generation (including my Dad) from the region you visited returned to becoming medical healers, but also had a strong connection to Kabbalah and metaphysical philosophy. Was this philosophy a coping mechanism for the harshness that they had endured as their reality? My Dad, alev ashalom, played the violin!

Your writing helped me to try to continue to fill in my own “family-gaps”. We are truly a multicultural society in America and this should never be forgotten. How did we get here? How can we, as older adults, leave our world a better place with Wisdom and Grace-of-character? The grand experiment of Democracy that our Founding Fathers created (with terrible conflict and bloodshed) is a brilliant construct for governance. We need to adapt our political system with positivity and hope to an infotech/biotech world. Unfortunately, there are other very challenging forms of government in our world.

I would encourage you to write more, and tell more about the importance of community and assimilation with “balance” that honors the past, but accepts our home…and creates a better tomorrow for the next generations.

This sounds like a fabulous trip, Sara! I’d love to go there. My father’s family came fromOdessa as well my brother went there and found their old house! They were bee keepers and my last name, Bortnick, means ,” Bee Keeper.”

I spent a summer in Tanzania teaching orphans with a global volunteer program. It’s very interesting. Very life altering and definitely go to ngora crater ( think that’s right) on safari before you leave. I fell in love with Africa and learned a lot about myself I’ve been back to Africa to teach in other places and for years, was very involved with education and following and supporting refugees. This all happened right after I read Leap! That book and you, helped me.

I’m glad you are going to Tanzania. What an adventure!research.

The part about Romania marching the Jews off to camps was surprising to me. And makes me very sad. I did not know. I had mistakenly believed the Romanians tried to help the Jews. Now I must do more research. Blessings to you,

Joey

I just finished reading Leap, followed by books written by several authors you interviewed. Starting Loose Change next. I enjoy your writing so much! This trip sounds fabulous. Thanks.

Fascinating, Sara. Thanks so much for sharing.

Hi Sara – I am always excited to read your blog. I have read and re-read many of your books a number of times, especially Loose Change.

PS I would not have hiked either!

Great trip and just as well you were out of the news cycle. Curious when you’ll be in Tanzania and with what travel company? I’m going in June and have many friends who have been traveling there in the last year. Must be the place to go.

Your trip sounds wonderful. Thank you for writing about it!

Hi Sara…as I was reading your travel-log/blog. I felt like I was on the trip with you. I started remembering all

my travels in my 20’s and 30’s-where today some of those countries are now decimated by war and authoritarian governments. One thing that stayed with me on my journeys was how many wanted to know about America. This was in the 70’s and 80’s. My travel companion and I felt like we were ambassadors and were the face of an America that many would not see first-hand.

Thank you so much. I have enjoyed your writing since Loose Change. Keep the observations coming!

P.S. I’m going to check out Wild Frontiers!

Sarah, thank you so much for your travelogues, particularly of places we are not likely to get to. It has been some years since our trip to Cuba with you, so reading your memoirs helps keep us in touch.

We now winter in Tucson, escaping the weather of the Mountains and Gold Hill. You are welcome to visit us either up there or down here! All the best, John and Cherry Sand

Thanks, John and Cherry. I thought of our trip to Cuba (before Obama went there) when I recently saw a documentary about the Rolling Stones playing there at the end of a tour in South America. Cuba was a stand-out for me.

Good on you, Sara!!!

(My own mother’s family came from Bialytserkva, near Kiev.)

I’m glad you got to go, and very glad you wrote about it to us so we could participate vicariously.

Blessings for the new year,

Eve

Great story!

Thanks, Jeff. good to hear from you.

Thanks for the intriguing and lively description -and of course it is retired people who have a greater desire for travel they have the luxury of having finished raising children/ended their careers, have time and usually enough money to see the world in a way we couldn’t, even as twenty-somethings.

What a great blog. Cheers. As you know, all four of my grandparents came from Odessa… Thanks for sharing

It was said that if you saw a Jewish boy on the street who was not carrying a violin case, “he played piano.”

I remember this being the case when I was growing up in New York in the 1950s as well.

“If something has been done the same way for centuries, that’s the reason to do it.”

While this may sound quaintly sweet–heritage, tradition and all–it is also a justification for all obsolete dogmatisms, irrational policies, and cruel superstitions.