Sara Davidson

|January, 20, 2020

I’ve known and been writing about Ram Dass, who died December 22, since the ‘70’s, when I read Be Here Now and decided: I have to meet this man.

I was in my 20s, an agnostic, having success with my writing, and miserable. “Woe is me,” was my mantra, inherited from my Hungarian grandmother. My husband would counter: “Woe is NOT you.”

It was a time when all around me, young people were lighting out for the spiritual territory, becoming vegetarians, learning to meditate and chant, and running to Chinatown to practice Tai Chi.

Some of my friends were quitting their jobs to take a 3 month round-the-clock training with Oscar Ichazo of the Arica Institute, who said that after the training, they would be enlightened.

A relative started following a Hindu swami who told her to rise at 4 a.m., take a cold bath, and do yoga. She urged me to do the same.

That was it. I decided to investigate and expose this mass delusion, writing a piece, “The Rush for Instant Salvation,” which ran on the cover of Harper’s magazine in July, 1971. But something had happened during my research. I’d found that I liked being around these gentle, spacey seekers who were working to cultivate honesty, joy, and love, but there was no way I could swallow their beliefs.

When the article was published, the editor asked if I’d resolved my ambivalence. “Yes,” I said. “I think there’s something valid in there, but I don’t know what it is.”

Then a friend gave me a square blue paperback that said on the cover: Remember Be Here Now, written by Baba Ram Dass with exotic calligraphy by artists at a New Mexico commune. I read the text in one sitting. Ram Dass’ story matched mine: he was a “neurotic, Jewish over-achiever” who’d found at a young age that his achievements and success left him empty.

As Richard Alpert, a psychology professor at Harvard, he’d been depressed and often had to throw up before giving a lecture. But the first time he took psilocybin with fellow professor Timothy Leary, he watched all his roles fall away, and felt a presence—an “I”—that was at peace and all knowing. When he and Leary were fired from Harvard for experimenting with LSD, they barely broke stride, moving to upstate New York to continue their research with psychedelics. But after each trip, each experience of higher consciousness, they’d crash back down.

After four years, Alpert was in a state of despair, and accepted a friend’s offer to travel across India. In the story that he would be retelling the rest of his life, he met his guru, Maharaji, who named him Baba Ram Dass. Dass means servant of Ram, or God, and Baba is a term of respect and endearment for an elder. (though Ram Dass was only in his thirties)

The most remarkable thing, to me, is that Ram Dass spent eight months with the guru, listening, watching him, studying, and doing mental and physical practices. He was learning Bhakti Yoga, which could be summarized in one phrase: see God in everyone, love everyone, serve everyone. In 1967, the guru told him to return to the U.S., where Ram Dass started speaking, teaching, and writing Be Here Now.

Eight months! That’s all. I know people who’ve been at it for decades—meditating, working on themselves, even teaching—and they don’t embody the wisdom and charisma that Ram Dass attained in eight months.

Was he born with a gift? Was it seeded in his DNA? Carried from a past life? (or some more rational equivalent?) He used to say that his ability and wisdom were grace, a gift from Maharaji, but in 2004, he told me he recognized that he’d been “using Maharaji—as an explanation for why I know what I know.”

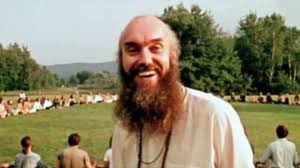

Ram Dass had always been a master at speaking; he could talk extemporaneously for hours, and convey esoteric concepts in a way that Westerners could understand. And he was funny; he’d run down Buddha’s Four Noble Truths and have the audience laughing all the way.

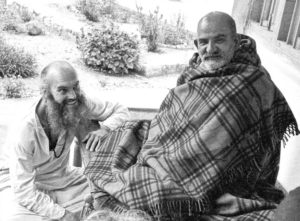

Ram Dass teaching young people in New Hampshire

As an individual, though, he wasn’t “finished” evolving. He still had moods and could be judgmental and waspish, but if the phone rang and someone needed help, he would grab the phone and stay with the caller until he’d guided the person to a calmer state.

When I decided I had to meet him, I obtained an assignment from Esquire to write a profile. Ram Dass had gone back to India, so I wrote him and a few weeks later, received a reply, saying my letter “felt good” and when he was in New York we might “share a moment.” He urged me to keep in touch through Marty Malles, who’d spent time with Maharaji in India and was a salesman of ladies’ underwear in Brooklyn. Marty took me to meditation groups and played me tapes of Ram Dass speaking. We heard rumors that he’d left India, heading for London and Scotland. We also heard that “his head was changing,” he might not speak or give interviews. After three days of futile trans-Atlantic calls, I had an intuition, and told Marty, “I bet he’s in Boston, seeing his father, right now.”

Marty picked up the phone, dialed a number and Ram Dass answered the phone.

“Hi,” he said to me, in a buoyant voice. “Did you finish your article?”

“No. I haven’t started it. I’d really like to see you.”

“Well,” he said, “I’m not living in time.”

“I could get in my car right now and drive to Boston.”

“You could, but you might get here and not find me.”

I said that wouldn’t bother me, but I had heard he wanted privacy and I didn’t want to intrude.

There was a long silence, and Ram Dass said, “If you can find me, you can have me.”

I was on the first shuttle flight the next morning. I had spent a sleepless night, deciding at 5 A.M. I could not go through with it and resolving at 6 A.M. that I would.

It was raining when the taxi dropped me at the townhouse in Boston owned by Ram Dass’ father, George Alpert, who’d been president of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad. I shouted through the intercom, “Is Ram Dass there?” I heard groans, shuffles. It was 9 a.m., a Saturday morning, and I had woken everyone up. Ram Dass opened the door wearing a white gauze shirt and pants and a jaunty plaid cap. He was taller than I had envisioned–6’2″. His face gave off a pink glow and his blue eyes were open so wide they seemed more vertical than horizontal.

“I took you at your word,” I said.

He nodded, and led me to the library, where he’d been sleeping on a convertible sofa. “This is where I hang out.”

I interviewed him for four hours, during which he talked about being in India this time with Maharaji. At first he’d been upset that he wasn’t alone with the guru. Dozens of young Americans had followed him to Maharaji’s temple, hoping to attain what Ram Dass had. Maharaji made Ram Dass “commander in chief of the Westerners,” told him to love everyone and always tell the truth. But the Americans were grating on Ram Dass’ nerves. “This one was whiny, that one was selfish, one was too messy, one was too neat,” he said. “It got so that out of 34 people, there wasn’t one I could stand. So I thought, I’ll be truthful about it.”

He stopped speaking to them, and for two weeks wouldn’t allow any of them near him. One morning, a boy brought him a leaf of food that Maharaji had blessed and Ram Dass threw it at him. Maharaji called him over and said, “Something troubling you?” Ram Dass said, “Yes, I’m angry. I hate everybody but you.” Maharaji asked why, and Ram Dass said, “because of the impurities which keep us in the illusion. I can’t stand it any more. I can’t stand it in anybody including myself. I only love you.” Then he broke into racking sobs. Maharaji sent for milk, and sat patting Ram Dass on the head, feeding him, crying with him, and saying over and over, “You shouldn’t be angry. You should love everyone.” Ram Dass said, “But you told me to tell the truth and the truth is I hate everyone.” Maharaji said, “No. A saint doesn’t get angry. Tell the truth, and love everyone. There’s only one. Love every one.”

Ram Dass looked at the group and saw standing between him and them this huge mountain—“my pride. For me to give up the anger, I had to give up my whole rational position, my reasons for being angry, without sitting down first and talking it over and winning a few points for my side.”

Maharaji sent him off to eat and called the others over and said, “Ram Dass is a great saint. Go touch his feet.” This made Ram Dass cringe and feel more furious. “I saw my predicament. I was going to have to do this all myself.” He cut an apple into pieces, went to each person and looked in that person’s eyes “until I found the place in him I loved.” Then I let all the rest wash away, silently. I fed them all, and when I was finished there was no more anger. Later I got angry again, but it went through very quickly because I saw that anger is only because you’re attached to what you were thinking a moment ago. It’s not real, it’s only a mind moment. Yes I was angry then. OK, now is now, and if you’re right here, everything starts all over again.”

It was still in the back room in Boston. Ram Dass said he was considering how best he could now serve. Maharaji had instructed him not to have ashrams, but when people managed to find Ram Dass, he would sit with them and ask questions designed to unleash the secrets and shame they were carrying inside. All the while, he’d be looking in their eyes repeating a mantra to himself. “Whatever they say gets completely neutralized the minute they bring it into my consciousness,” he said. “Because I don’t care. I know it’s not real and they feel this tremendous re- lease.”

I wandered around Boston the rest of the day in a very unfamiliar frame of mind. This was the first time I’d heard—and understood—that thoughts and emotions were not set in concrete but more like clouds rolling by. Ordinarily, everything I saw or heard came into my awareness with a judgmental tag: that face is ugly; that color is nice; that man looks interesting. But this afternoon everything was coming in directly, without the tags. The people on the street, the orange sunset over the harbor, the piped Muzak in the elevator, the smell of frying food—everything simply was what it was, and the play of patterns, rather than any single image, was breath-taking.

With Ram Dass in 1973,

at funeral of Alan Watts

I flew home the following day with thirteen hours of taped interviews, and shut myself off from the world. The words poured out, sixty pages in two weeks, and I believed that everything I had written before was in preparation for this. I turned down an assignment from The New York Times Magazine to go to Cuba to interview Castro on his forty-fifth birthday. My husband said I was nuts, I was losing a major opportunity, but I felt certain this was more important to me. When I finished the article, I dropped it at Esquire and went away for the weekend. A few days later, my editor, Lee Eisenberg, called and asked me to come in. There were “problems,” he said. I wore a long lavender dress and my hair in a braid down my back. “You look beautiful,” he said, and I knew it was over. He fidgeted. “We can’t publish the piece. Ram Dass comes off as silly and simplistic, and your willingness to embrace his ideas is incomprehensible.” I said I’d told him in advance that this would not be a hatchet job. He shook his head. “You’ll thank us later for not printing this. It would destroy your credibility.”

I asked my agent to send the article to other magazines, but the responses were similar: “Annoying.” “Foolish.” “We like Sara Davidson the journalist but we do not like Sara Davidson the convert.” While many of my friends were “on the path,” the gatekeepers in the publishing industry were, as I had been before, resistant, even hostile.

I decided not to write about spiritual matters again. But months later, I got a call from a colleague, Min Yee, in San Francisco who was an editor at Ramparts, the leftist political journal. He asked what I was working on.

“Well, I just spent five months working on something no one will publish.”

“Give it to me, I’ll print it,” he said.

“No you won’t.” I laughed. “It’s not for Ramparts. It’s about God.”

He told me to send it anyway, and Ramparts published the story in full. Looking back, years later, after Be Here Now had sold more than two million copies and Ram Dass had become an icon, I wondered if the editors at Ramparts had been prescient.

I stayed in touch with Ram Dass and wrote more pieces about him in the following decades. In the 80’s, the country was caught up in a fever of accumulating wealth, and many who’d been seekers turned their attention to making money and raising families. Ram Dass stayed the course, but fell off the cultural radar screen. He concentrated on service, working with the homeless, prison inmates, and people facing death, and set up a foundation to treat people with blindness in third world countries.

He wrote seven more books, and in 1997, he was working on one about aging and dying when he had a stroke, which left him with aphasia—difficulty speaking and accessing words—and his right side paralyzed.

He rewrote the book, with a friend’s help, and when it was published in 2000, he gave a talk—speaking slowly, with many pauses—at the church of St. John the Divine in New York. It felt like a reunion of a great many people he’d inspired and taught, who’d now become doctors, artists, teachers, and business executives. I found myself, once again, taking notes, and wrote a piece that was actually published this time, in the New York Times Magazine. The culture had caught up with Ram Dass.

With the support of caregivers, he began traveling the country again, speaking and leading retreats. He’d come to see his stroke as “fierce grace,” because it had made him more compassionate, humble and accepting. He had constant pain on his right side and tendonitis in his left shoulder from overusing it. “But all I have to do is go inside…” he said, pointing to his chest, “and there’s peace.”

His guru had died, but Ram Dass wanted to go to India again and pulled it off, despite the wheelchair. Flying home to California, where he was living, he fell sick, but immediately left for Maui to speak at a retreat. Friends urged him not to go, but he said he didn’t want to “welch on my agreement.” At the end of the retreat, he collapsed, was rushed to the hospital with a severe infection, and nearly died. After that, he resolved to not get on an airplane again. “I’m going to die in Maui.”

With Ram Dass in Hawaii

I visited him there numerous times, especially in 2010, when he discovered that he had a son—a 54-year-old banker in North Carolina—that he’d never known about. I wrote a Kindle single about how it had happened and the effect on Ram Dass. I was planning to visit him this February, when I received word that he had died on December 22. He’d been hospitalized again with an infection that was spreading, but was back home, with his caregiver/manager, Kathleen Murphy, whom he’d named “Dassima,” and his friend and literary collaborator, Rameshwar Das. When I spoke with the latter, he said Ram Dass had “died the way he wanted to: awake, at home, in the daytime.” He’d been having trouble breathing and at one point, Rameshwar Das said, “he gasped a few times and was gone.”

The news was posted instantly on, yes, Instagram, and within hours, there was an outpouring of love, sadness and gratitude from around the world. Almost every person who does yoga or has a spiritual practice today was influenced, directly or indirectly, by Ram Dass. He insisted to the end, however, that he was not a guru. On one of our visits, he told me he sometimes sees himself as “the kindergarten teacher,” who’d taken people on their first steps along the path. “But I’m not a guru.”

Why? I’d asked.

“The guru is God-realized and clear. He has no attachments and nothing in his personality is in the way.”

“Would you like to become realized in this life,” I asked?

He shut his eyes, letting the question sink in, waiting for the truth, not just a quick response. After a time, he said, “Yes,” and opened his eyes. “Then I would be able to help people so much.” He nodded. “So much.”

I saw that, for me, being realized had meant becoming free from the wheel of suffering. But in the Buddhist and other traditions, one who becomes enlightened chooses to turn back to the world, to incarnate again in order to help others. Until everyone is free. Everyone.

When Ram Dass learned about a couple whose 11-year-old daughter had been raped and murdered, he took it on himself to write them a letter, which has often been viewed as an exemplary, heartfelt, and powerful response to such tragedy. It can be read here.

What a wonderful tribute! Thank you, Sara.

Love,

Ren

Sara, I always love your writing, and as a Buddhist practitioner especially appreciate this piece. I never knew Ram Dass personally and haven’t read Be Here Now, but now I feel I have come to know him a little through your account of his (and your) struggles and deep humanity. Thanks.

I am totally blown away by this story. Thank you so much for sharing it. You are incredible. I’m off to buy the Kindle Single and eager to read it!

Oh, Sara,

I LOVED your blog today, but more than that, it was/is IMPORTANT to me. I have a full day of work but when I saw your blog was about Ram Dass, I stopped everything to read it. Ram Dass was/is so important to me, as he was/is to so many. Your recollections fill me with joy and with Grace. My day is better because of your blog. My life is better because you are in it.

with love,

~ richard

Awww, Richard. So sweet. My day is better because of you.

As always, beautifully written, and thank you for sharing this with us. His love and teachings shine through and I welcome the reminder! AND, love, love, love that photo of the two of you in the pool.

Wonderful to hear from you, Arielle. AND, I just added another photo on my blog page, taken in 1971 at the funeral of Alan Watts. Ram Dass had invited me to go with him, and I told friends later, I felt like “Queen for a Day.” Are you old enough to remember that tv show? You can see the photo at https://www.saradavidson.com/blog/2020/01/ram-dass-does-a-saint-get-angry.html

Since I heard of his death, I’ve been waiting to see what you’d say. As always, you said it perfectly. Thank you.

Sara, this is so beautiful and helpful, just what I needed right now. And Ram Dass’s letter to the grieving parents is a keeper. Thank you.

Thank you Sara for this blog. I’ve always loved ‘Loose Change’ when I read it many years ago and recently found a used copy and reread it. I sort of missed the ’60s as I was a little older at that time and from rural midwest where things moved more slowly. ‘Be Here Now, Remember’ also had a huge impact on my life when I discovered it back in the 70s. I had the distinct honor of seeing Ram Dass some years ago at Tara Mandala in Pagosa Springs, CO where he was a guest of Tsultrim Allione who had known him from back in the 60s when she was also in India. I feel blessed to have had that short few hours in his presence and hearing him speak. Thanks again.

Wonderful piece on Ram Dass! Very moving and honoring of him. Thank you. Fun to see the pic of you and he in Maui. I also was glad to hear your article on Ram Dass finally got published. I will look that up and read it soon. Thanks for including the link for the letter he wrote to the parents of the raped and murdered daughter! So touching.

I so appreciate your writing, Sara, and constantly reference Leap for inspiration (would love a part 2!) and have read Loose Change several times over the past 40 years. Thank you!!!

Thanks, Gail, for your kinds words. They mean a lot! I just added a photo to the blog of me with Ram Dass in 1973, at the funeral of Alan Watts. Can’t believe what I was wearing:

a leotard, long skirt and shawl. All gone.

https://www.saradavidson.com/blog/2020/01/ram-dass-does-a-saint-get-angry.html

I love it, outfit and all (I came of age in the 70s!). Also, how cool that you attended Alan Watts’ funeral and got to see Ram Dass to boot. Thanks for sharing this picture.

Thank you for this moving article. What a wonderful tribute to an amazing person, who touched so many of our lives.

Here’s a Link to a short 3-4 min talk radio interview for Connectingpoint a daily series I created &&!!

and produced. The excerpt is from a half hour episode. It’s married to Video imagery and music.

Ram Dass, on conscious aging was originally recorded in LA at the Whole Life Expo in Pasadena,

just a few months prior to his stroke https://youtu.be/Gy7KEqcp2D8 I hope you will enjoy.

Thanks, John. I look forward to hearing it.

From what Michael Pollen has written about his experiences taking LSD, LSD does bring some if not all users to their third eye just as it did with Ram Dass. For most of us who meditate, we work at getting there without intoxicants of any kind. The goal is being soul and seeing it in others. It is love.

Thankfully, at all times there is a living saint somewhere in the world to help us learn that we are soul.

The path that I am on is not a religion. It is true spirituality called “esoteric.” Religions with their practices and traditions are “exoteric.” I’m glad I found this true path and can continue practicing Judaism and seeing the connections between the basics of all religions with meditation.

I’m curious what Ram Dass’s Maharaji’s name was. Maharaji is a title.

Hi Linda, wonderful to hear about your esoteric path. The guru’s name was Neem Karoli Baba. There is a shrine to him near Taos, N.M., where Ram Dass’s ashes will be interred. Hope our paths cross one of these days.

LSD is not an ‘intoxicant.’ It is an opener of gates, particularly of the Third Eye. But it’s only an opener. You have to learn how to open that ‘gate’ by yourself.

Mediation is that Opener.

Dear Sara,

Thanks for your insights and your sharing of them.

(You and I communicated years ago regarding Elisabeth Targ, my unofficial step-daughter. She became interested in researching spiritual healing after Spirit worked through me for the healing of her father, Russell Targ. He is alive and well today, while the healing love of Elisabeth works through me from a more powerful domain.)

Your enduring relationship with Ram Dass trumps any writing assignment you might have been denied.

How wonderful that you had such good discernment of the subtle inner urge for truth!

I send you warm wishes,

Sincerely,

Jane Katra

Hi Sara,

Terrific! Bravo.

See you soon.

Love, Tina

Thank you for the lovely piece, Sara.

Ram Dass was our consultant on the feature film Resurrection and when i saw him again after the stroke we spoke of making a feature film about conscious dying. He was luminous and hilarious. I will miss him. And he died consciously. Beautiful.

Renee, Resurection was one of my favorite films as a young girl-it affected me deeply. I never hear of it anymore – it is like a wonderful and vague memory that you feel like you alone had. Grateful to you for making this feature film and to hear Ram Dass contributed to it.

Sara – I’m sure your open-heartedness allowed you to get close to people and be such a good journalist, but I noticed also that your (and Ram Das’s) search for enlightenment came about because you were suffering, and miserable. What about the more practical and possibly more efficient solutions to misery: time, open-heartedness and positive thinking? Be here now etc. I guess there are no good answers for how people should try and find answers – I’m just writing this because you made me think.

Such a fascinating, personal and heartwarming tribute to a beautiful soul. Thanks, Sara. 💚 nance

Oh Sara, evertime I read something that you’ve wrote, I feel the generational-connection of purpose shine through–and the emotional “attachment” to it. (I do love a paradox!)

My copy of Be Here Now is one of the last books that I’ve managed to hang on to as I cull and let go of heavy-to-move, dust-catching hard copies that I no longer wish to take up space. What is so important to me about that now taped together, poured over and ragged collection of free-flowing thoughts?

It’s difficult to explain but I think that you did a great job of it.

Thanks BE from my Heart to Yours and Ours

Thank you for that great piece, Sara. I was a devotee back in the New Age of the Old Eighties, and he lit my way for a good while. I had always wondered what became of his special life. I met him when he “played” Vanderbilt at some point in the ’80s. The man just oozed gentle kindness and wisdom.

Man was that heart felt. sometimes your life sounds like Forest Gump-at the right place at the right time-not all luck but good instincts.

See you soon.

Dean

Thank you for this sharing into this man. I feel like I know him a little better because of your words about him. You have opened me in some inexplicable way that I will be watching over the days of my life.

Donald Theiss

Oh Donald, thanks so much for your lovely comment. It means so much to hear how the words about Ram Dass touched you. He was such a key influence in my life.

Thank you for your post on Ram Dass’ life and legacy.

I haven’t read Leap yet, but I’ve read Loose Change and Real Property.

Is Leap in bookstores?

Hi Beth, thanks for your note. All my books are available online, on Amazon.com, and also on my website, http://www.saradavidson.com. Click on “Books” to read an excerpt from each one. Leap was published some years ago, so it wouldn’t still be in bookstores.

I lived and traveled with Ram Dass in India in 1970-71. One day we were walking on the beach in Jaganath Puri and he confided he regretted telling everyone about Maharajji as now he had to share him with everyone, and he didn’t really like all these people. In 2011 I met him again in Maui at the 40th reunion of our time with Maharajji, and he said he didn’t know why people came to see him.

I said, “Because they feel your love.”

“But I don’t love them,” he replied.

“Well, people fee it,” I insisted.

“Well, they must be feeling my love for Maharajji.”

Beautiful piece of writing, Sara. He was a gift to so many of us back then and now. Thank you for keeping me on your subscription list. You speak eloquently to our generation.

Elizabeth Lord

Thanks, Elizabeth, for your lovely words. It means so much–keeps me going, despite the frightening number I’m about to turn on my birthday tomorrow.

Oh dear – does it have a zero in it?

You are like fine wine – better with age 🙂

Hello Ms. Davidson, I am writing a Farewell article about Ram Dass for Stanford Magazine. Do you have any info to share about his time at Stanford?

Thanks and regards,

John Roemer

415-706-0593

I think your best source for RD’s time at Stanford is his autobiography, Being Ram Dass, just published. I know little about it. He told me he had failed most of his exams because of performance anxiety, a fear of performing on tests, which was the subject of his thesis. But he was popular with students, and was asked to teach classes, which shocked the professors who’d failed him in their courses. the Good luck with your article.

It is indeed a privilege to spend time with Ram Dass. I agree with Ram Dass, your writing “felt good” 🙂 His simplicity in explaining complex concepts was remarkable. Even short quotes from him were more powerful than some lengthy discourses. I’ve compiled a few quotes here: https://lifeism.co/20-best-inspirational-ram-dass-quotes/ Let me know if you enjoy them 🙂

Thanks for the quotes. The one that hit me most strongly is: “Everything changes once we identify with being the witness to the story, instead of the actor in it.” I tend to identify with the melodrama of the actor. This is a great reminder.

I love that one too. It also tugs at the big question, “who am I?”

We are the consciousness experiencing life. So beautifully explained.

Thanks for responding to the comment 🙂

I think you might enjoy the Kindle Single I wrote, “Ram Dass Has a Son,” which is the story of how RD discovered, at age 70, he had a son he’d nver known about. The son was in his 50s, lived in North Carolina, looks quite like RD but had never heard about him. The son and said he didnt have “a spiritual bone in my body.” This forced RD to revise his ideas about love and family. Eventually they became quite close. You can get it on the Kindle store for $2.98 and read it on any device. If you read it, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Warmest,

Sara

I was not aware of the book, thanks 🙂

It’s on my reading list! I’ll be back with my notes once I’m done.

I touches my heart. Thank you

Hello Sara and Sara blog readers,

That letter. It’s God’s poetry. And it’s a foot in Earthly muck. It’s nothing such parents want to hear. And everything they want to hear. He offered himself. Simply. It’s Love. Thank you for sharing.

I didn’t travel your particular path. Never read a Ram Dass book. Just two days ago I looked him up on YouTube and listened to a talk he gave. I enjoyed his splay of humor and ease.

I discovered you, Sara, through friends of a group I belong to that mentioned an article you wrote about Joan Didion. I read it and was engaged. I tried to read her Year of Magical Thinking some little bit ago but couldn’t hang with it, but Joan’s name and that book came up in conversation with my brother because his son, my nephew died unexpectedly in his sleep a few months ago and my brother is reading the book. One bread crumb after another, and I finally asked myself “who is Sara Davidson? And what has she written?” I am now, I think, a Sara Davidson completist having read all the books I could find that you wrote.

This was a wonderful ‘description’ of his life. Thank You.

Even though I’ve read “Be Here Now” many times, it is still a struggle. But then, Ram Dass acknowledged that as well. Enlightenment is about the not having the need to say/believe that you are enlightened. That was why he was a Guru in the best of all possible definitions.

Thank You once again.