We’re at the Indus Valley Ayurvedic Center (IVAC) in tropical Southern India to have Pancha Karma, a cleansing and rejuvenating therapy. Two long-time friends have convinced me to do this: Andrew Weil, the Harvard-trained physician and best-selling author who advocates Integrative Medicine, combining Western and alternative remedies, and Kathy Goodman, an art dealer from Manhattan who has a strong interest in healing.

Since Ayurveda is currently being imported to this country, Andrew wants to experience the treatment first-hand at the source.We pick up the glasses of ghee. I intend to chug it down but gag at the first mouthful. It’s thick and viscous, like motor oil. Andrew and Kathy struggle to force theirs down, and when the doctors leave, Andrew throws up his arms. “Western and Eastern medicine have parted company today,” he says. “I can just feel the butter clogging up my arteries.” We’ve been told the ghee will loosen toxins in the body just as soap loosens dirt on dishes, then wash the toxins out of our bodies. Andrew says, “That could all be pure fancy.”

Ayurveda, a complex system of medicine that arose in India 5000 years ago, is being offered in modified form at American spas and healing centers, such as Canyon Ranch in Arizona and Deepak Chopra’s center in La Jolla, California.

Kathy is the only one of us who’s tried Ayurveda before. In 1995 she was suffering from chest pains that Western doctors couldn’t diagnose. She met an Ayurvedic doctor who took her to Poona, India for Pancha Karma, which cured her symptoms and left her in a state of peak health. She persuades me to come by describing how four therapists will massage each person at once with special oils. I agree, thinking I’ll spend a week being pampered at a spa and between massages, I’ll hike in the hills and shop for silk. The other factor compelling me is that for months, I’ve had painful stomach cramps that doctors have been unable to cure.

While many Ayurvedic clinics in India are housed in tumble-down buildings with questionable sanitation, Andrew picks out a luxurious center, which even has a web site. When I click on Pancha Karma, though, I find that it consists of five therapies: vomiting, purgatives, enemas, nasal infusions and blood letting.

Blood letting! Kathy says we won’t have blood letting, and any discomfort will be well worth it. “When I came home last time,” she says, “my skin was shining and my digestion was perfect.”

The notion of going to India to become healthy, of course, is an oxymoron. To prepare for the trip, I have five inoculations recommended by the Centers for Disease Control: typhoid, hepatitis, influenza, polio and tetanus. Kathy and I fly to Delhi ahead of Andrew and after ten days, my throat hurts from inhaling smoke and my eyes burn from the smog. Andrew and I have contracted colds and are coughing when we settle into a taxi for what the IVAC brochure describes as “a convenient two and a half hour drive to Mysore.”

It’s the taxi ride from hell. We set out at ten p.m. when giant trucks are on the road, belching smoke and honking their horns. Bumper stickers on the backs of the trucks say, “Horn, please.” Honking constantly, our driver darts around trucks, cars, wagons pulled by oxen, mopeds and auto rickshaws-motorized carts with three wheels. The driver swerves to avoid hitting cows, goats, water buffalo and camels trotting loose on the road, seemingly with no human in charge.

It’s one a.m. when we turn up a gravel road and stop before a large building with coconut palms silhouetted against the sky. We step out into silence. A single file of women in saris come walking down the steps. They pick up our bags and show us into what seems a palace: a white marble staircase curves around an indoor fountain. Moonlight streams through the blue glass panes of an atrium, turning the cream-colored walls shades of lavender and blue. Our rooms have canopy beds, marble floors, sandalwood closets, ceiling fans and sumptuous bathrooms with a European toilet and bidet.

DAY ONE

At breakfast we find we’re the only guests presently staying at IVAC, which opened in 1999 and has a staff of fifty. They can accommodate ten residential guests and a dozen who stay at nearby hotels. While some come from India, the majority are from Europe, the U.S. and Japan, where Ayurveda is popular.

After we eat dosas, light pancakes with fresh papaya and yogurt, we meet the founder of IVAC, Talavane Krishna, M.D. A tall, soft-spoken man of 52 with a characteristic Indian high-pitched giggle, Dr. Krishna was an anesthesiologist for 20 years in San Diego and Las Vegas. In his forties, Dr. Krishna began to develop kidney stones, sciatica and gastro-intestinal problems. “I took so many Western medicines and none of them worked,” he says. He turned to Ayurvedic remedies and his health improved. Seeing that Deepak Chopra was beginning to popularize Ayurveda, Dr. Krishna decided to build a center in Mysore that would have five-star accommodations and “meet the standards of discriminating international clients.”

He hired cooks to prepare food according to Ayurvedic principles. He trained young male and female therapists to give massages, and set up research programs to “validate ayurvedic therapies and bring Ayurveda into mainstream medicine.”

After lunch, Dr. Krishna, who’s called “our President” by his staff, introduces us to N.V. Krishna Murthy, (pronounced Krishna-murty) an Ayurvedic physician who will supervise our pancha karma. Krishna Murthy, a thin, simian man who wears a white coat over Western clothes and black Speedo sandals, interviews us and prescribes purgatives. He explains the basic principles of Ayurveda: there are three doshas or body types: vata, pitta and kapha. Each person has a unique blend of the three doshas and good health reigns when the doshas are in balance. Later we will learn that Andrew with his large frame and deep voice is predominantly kapha. Kathy who’s small and moves quickly is vata. With my medium build and gait, I’m pitta.

The chief cause of disease, Krishna Murthy says, is ama, undigested food particles which lodge in the body as toxins. To rid the body of ama, we will go through three stages of Pancha Karma: “preparation, operation and post-operation.” For the first three days, we’ll have oil massages and swallow medications designed to bring all toxins to the stomach. “On the fourth day,” he says, “we flush them out.”

He passes out sheets with the rules for Pancha Karma. No exercise or exposure to sunlight. One must be celibate, speak in low tones, “confine to the bed” and avoid anger and sorrow “because they aggravate the doshas.”

We’re on bed rest and can’t leave the palace? Kathy protests that when she had Pancha Karma before, she was free to come and go as she wished. Krishna Murthy says we must observe the rules to achieve maximum results. We confer and decide: since we’re here, we’ll go with the program.

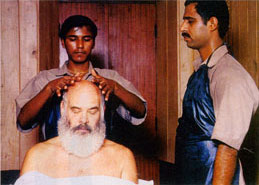

At five p.m., a therapist wearing a dusky pink, pajama-like uniform escorts me into the treatment room. She asks me to remove my clothes and lie down on a polished wood table. Working in unison, two therapists rub oil on my limbs until I’m slipping and sliding about. The women, who have a sweetness about them, were trained for a year before they were allowed to work on clients. “They’re the most important people in the center,” Dr. Krishna says, “because they touch the guests.”

A third women administers shirodara, a treatment in which she drips warm oil onto a spot in the center of my forehead alleged to be the third eye, the center of intuition and creativity. I’m apprehensive; the steady dripping sounds like Chinese water torture but as it begins, I find myself sinking into deep relaxation. Precision seems critical in this treatment. If the oil hits half an inch above the targeted spot, the effect is minimal but when it hits the sweet spot, it sends currents of sensuous warmth clear down to the toes.

In the evening, Krishna Murthy makes rounds, accompanied by three interns who’ve recently graduated from the Ayurvedic College in Mysore. As Krishna Murthy speaks, the interns wag their heads from side to side in the Indian form of nodding. Krishna Murthy checks several pulses in our arms and looks at our tongues. He says mine is coated with ama. I tell him I have a bad cold. “Tomorrow you will be fine, madam,” he says. I doubt that; the cold feels two or three days from clearing up. After dinner, one of the interns brings me a remedy-a spicy brown paste to eat before sleeping.

DAY TWO

The cold is gone.

We’re not allowed to eat any food until the ghee we drank at dawn is “completely digested.” Dr. Krishna insists that ghee is not harmful to the heart or arteries. “If you take ghee in the right amount it will lower cholesterol and cure angina.”

Andrew is unconvinced. “That flies in the face of accumulated knowledge of the past century!”

We spend most of the day reading in wicker chairs on the veranda. Although it’s eighty degrees, a female staff member brings us face coverings that look like ski masks, gloves and socks made of scratchy wool. I refuse to wear them. “You must keep warm,” she says. Andrew dutifully puts on the ski mask and after two minutes, rips it off.

We’re truculent patients, scrutinizing each procedure, questioning every rule. We ask Dr. Krishna why we can’t take naps during the day. He says, “If you sleep, the body slows down and ama will build up.” When he walks away, I ask Andrew, “Do you believe that?”

“Do you believe in ama?” Andrew says.

At evening rounds, Krishna Murthy asks, “What was your response to the ghee?”

“I have stomach pains and I’m bloated,” I say.

“You are fine, madam,” Krishna Murthy says.

Fine? I’m unable to button my jeans.

“This is perfectly normal.”

He launches into an explanation of how ghee penetrates the seven tissues of the body. It strikes me that Ayurveda is a system of numbers and interlocking categories. Ask a question and you’ll receive a ritual recitation of numbers of elements that break down into sub-parts. Health is determined by the five elements which combine into the three doshas which have ten pairs of qualities and produce seven constitutional types. One of the ancient sages, Charaka, even defined four types of lives: creative, destructive, happy or miserable.

DAY THREE

“Our President would like to give you a complimentary treatment,” the intern says. The treatment, Patrakhizhi, is a two-hour massage given by six therapists. Krishna Murthy prescribes specific herbs to balance our doshas. Staff members pick the herbs from the center’s organic garden, clean and fry them in oil, then strain the oil and tie the herbs up in small pieces of muslin.

In the treatment room, six women take their posts. One pours oil into a wok-like pan on a burner. A second carries in a tray with the packets of herbs and sets them in the oil until they’re warm. Then four women take a packet, squeeze the oil onto my skin and pound it in. They work like a surgical team, pouring oil and pounding until there’s a pool several inches deep on the table and I’m coated like a salad.

“I’ve never conceived of so much oil!” Andrew says when we gather for lunch, which, like all meals at the center, consists of rice, lentils, vegetables and fruit. I’m still having stomach pains and consider aborting the treatment, but Kathy says, “You’ve come this far, you should see it through.”

Andrew reaches in his pocket for the tickets we’ve purchased on the express train to Bangalore on Friday. “This is our exit visa,” Andrew says, waving the packet. “I feel joy just holding it. I want to be home with my dogs. I want to cook my own food with olive oil instead of ghee. Oh happy journey-home!”

We dread the visit of Krishna Murthy. The President says Krishna Murthy is highly respected in Mysore, where he runs a clinic and lectures at the college, but he doesn’t seem to listen to us. He recites his litany of numbers, types, branches and parts, after which we understand nothing. He insists we are fine. Kathy tells him she’s been unable to sleep in Mysore. He tells her, “To sleep will be solved today, sir.”

“I hope so,” Kathy says, “because it’s been a lifelong problem.”

He says she must wash her arms and legs, then sit in bed and breathe fifty times, silently saying the mantra “so” on the in-breath and “hum” on the out-breath. “Then tell your body, please go to sleep.”

Kathy and I follow his instructions that night, washing our limbs, breathing fifty times and asking the body to sleep. Then we turn off the lamp and lie awake most of the night.

DAY FOUR

My birthday. Every member of the staff comes up to give me flowers and say, “Many happy returns.” After my massage, the young women vie to be the one who will bathe me and wash my hair on my birthday.

The center has asked Andrew to give a press conference for Mysore reporters on the state of American medicine. Despite his reservations about our treatment, Andrew gives a warm-spirited talk. One reporter asks why he’s in Mysore. “To learn about Ayurveda,” Andrew says, adding that he thinks Western medicine is “collapsing because it’s too expensive and too dependent on technology. It works well with acute illness but it’s not very good at treating chronic conditions, such as asthma and irritable bowel syndrome. Traditional medicines such as Ayurveda are often more effective.”

That night, Krishna Murthy prepares us for our “operation.” He says he’ll give us medicine in the morning so “all ama and toxins will arrive in the g.i. tract and be flushed out. There is no need to scare. Nothing will go wrong. You should speak to your stomach and mind so that only waste products are going out. No body parts.”

DAY FIVE

The interns bring us cups of black paste, and I’ll spare you the details of what happens after we force down the paste. We spend most of our time on the veranda, playing cards to distract ourselves.

At mid-day, Krishna Murthy appears with the three interns following like ducklings. He asks Andrew, “You see what a gentle procedure this is?”

“Yes,” Andrew says.

I glare at Andrew. I’m bloated so badly I look seven months pregnant.

Krishna Murthy says I’m fine.

Kathy, who has intermittent hypertension, says she’s concerned about her blood pressure. “My head feels light.” He takes her blood pressure and although it’s elevated, he says there is nothing to worry about. “When toxins go out of the body, people experience different things.”

By six that night, Kathy’s lying on her bed looking ashen. When Krishna Murthy arrives, she says, “I want you to listen to me. I know what it feels like when my blood pressure is too high. Something in that preparation you gave us wasn’t good for me.”

“Don’t worry, Madam. Whatever may happen, we are ready to face it.”

Kathy narrows her eyes. “I don’t want any more ghee.”

“And I don’t want any more ghee!” I say.

“I don’t want any salt in my food either,” Kathy says.

Krishna Murthy folds his arms. “But madam, without salt, your food will not be tasty.”

“I don’t care if it’s not tasty! Salt is bad for my blood pressure.”

“Please,” he says. “My sincere request is that you cooperate with the purification therapy. If you just relax, tomorrow your blood pressure will be normal.”

When he leaves, Kathy tells us she’s frightened she may have a stroke. Andrew says he’ll monitor her but doesn’t believe that will happen. “Once the substance leaves your system, you’ll be okay.”

That night, Dr. Krishna, “our President,” brings in a troupe of Indian musicians to play ragas “that will pacify the doshas.” I can’t say what happens to the doshas but the music pacifies us and we actually sleep.

DAY SIX

When I wake up, my stomach is flat and I’m free of pain–a state which, to my surprise, has continued to this day. Kathy’s blood pressure is normal. We ask Andrew how he feels. “Great,” he jokes, “but I felt great before I flew here.” We all look many years younger than when we arrived. Krishna Murthy takes our pulse and announces: “All three doshas are in balance. We are releasing you tomorrow.”

We spend the rest of the day shopping and exploring the Mysore Palace, which we find riotously colorful and more inspiring than the Taj Mahal. That night, “Our President” has his personal cook prepare a banquet for us: dozens of dishes served on a banana leaf enhanced by elegant table ware of silver and crystal. Then we watch “Ghandi” on his large-screen t.v.

DAY SEVEN

The entire staff gathers on the veranda to say goodbye. Tropical birds are calling in the mango trees and a warm wind rustles the leaves. The female therapists in their pink uniforms encircle Kathy and me, placing wreaths of fragrant tulsi leaves around our necks.

In the taxi, Kathy asks Andrew how he’d evaluate Pancha Karma. “I feel renewed,” he says, “but it’s hard to separate the effects of the treatment from the whole experience of being in India, especially being taken care of and forced to relax for a week.” He adds, “I like the idea of detoxifying and giving the body a rest.”

“Would you do it again?” she asks. The Ayurvedic doctors suggest a cleanse once a year.

“Yes,” he says.

“No,” I think. Then I remember my last treatment: a massage with herbs and warm water, given simultaneously with shirodara. The procedure took me to the brink of sensory overload: warm oil dripping on the forehead while eight small, supple hands rubbed scented water on my limbs. My skin had become so sensitive from the treatments that the tingling pleasure of the dripping oil was almost unbearable. When it ended, I felt dizzy and intoxicated. The therapist smiled as she helped me sit up. “People say it’s like going to heaven and they don’t want to come back,” she said. “But we must.”

For more information on Dr. Andrew Weil, log on to www.drweil.com

For more information on Pancha Karma and the IVAC Center, log on to www.ayurindus.com.